From Cambridge University Library, Manuscript Gg.1.2, a compendium of grammar, προγυμνάσματα, etymologies, &c. These poems come after the Περὶ Συντάξεως of George Pardus (a.k.a. “Gregory of Corinth”), which will protect the gentle reader from solœcisms, barbarisms, and other career-breaking faux pas: for example, it will remind you, if you even need reminding, to say ἀνέχομαι (with the dative, of course) rather than—mon Dieu!—βαστάζομαι. A marginal gloss wrongly attributes that work to Constantine “Michael” Psellus, a mistake repeated by what I believe is still the standard catalogue to the library: Hardwick & Luard no. 1397.12 (vol. 3, pp. 11sq.; online here).

For help even beyond what Ψευδοψελλός can offer, we must call upon higher powers. As far as I know, these haven’t been published elsewhere.

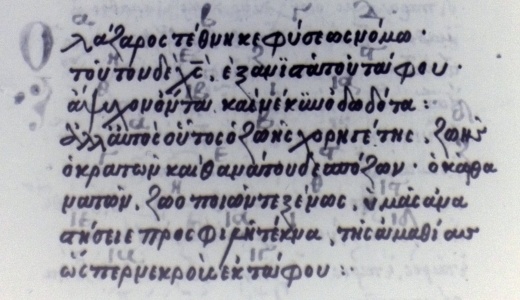

256v The top half of the page is an abbreviated run-through of nominal morphology. The second half has the following poem:

Ὁ Λάζαρος τέθνηκε φύσεως νόμῳ·

τοῦτον δὲ Χριστὸς ἐξανιστᾷ τοῦ τάφου

ἄψυχον ὄντα καὶ νέκυν ὀδωδότα:

ἀλλ’ αὐτὸς οὗτος ὁ ζωῆς χορηγέτης, ζωῆς

ὁ κρατῶν καὶ θανάτου δεσπόζων, ὁ καὶ θα-

-νατῶν ζωοποιῶν τε ξένως, ὑμᾶς ἀνα-

στήσειε προσφιλῆ τέκνα, τῆς ἀμαθίας,

ὥσπερ νεκρὸν ἐκ τάφου.

Most of the words are marked (presumably numbered) with a superscription in another color, in a way we can derive no meaning from: Α (Λάζαρος), Β (τέθνηκε), Γ (φύσεως), Δ (νόμῳ), Η (τοῦτον), Ε (Χριστὸς), Ζ (ἐξανιστᾷ), ΣΤ (τοῦ τάφου), Θ (ἄψυχον), ΙΒ (ὄντα), Ι (νέκυν), ΙΑ (ὀδωδότα), Α (αὐτὸς), Β (ζωῆς), [there may be a faint marking over χορηγέτης, but we can’t be sure], Δ (ζωῆς), Γ (κρατῶν), Ε (καὶ θανάτου), ΣΤ (δεσπόζων), Ζ (καὶ θανατῶν), Η (ζωοποιῶν), Θ (ξένως), ΙΣΤ (ὑμᾶς), ΙΕ (ἀναστήσειε), ΙΑ (προσφιλῆ), Ι (τέκνα), ΙΔ (ἀμαθίας), ΙΒ (ὥσπερ), ΙΓ (τάφου). …An αἴνιγμα for the clever.

–

257r This page is wholly taken up by another poem, a prayer for a young writer, with similar markings that we won’t reproduce here (puzzle-solvers can enlarge the photo), but with some verbal interlineal annotations as well. The poem itself, in fairly large letters, runs:

Κύριε Ἰησοῦ Χριστέ, ὁ θεὸς ἡμῶν ὁ ἀσπόρως

εὐδοκήσας τεχθῆναι ἐκ τῆς ἁγίας

θετόκου καὶ ἀειπαρθένου Μαρίας

ταῖς πρεσβείαις αὐτῆς καὶ τοῦ (4)

χρυσορρήμονος Ἰωσήφ, φώτισον τὸν νοῦν τοῦ νέου

τοῦ νῦν ἀρξαμένου τοῦ σχεδογραφεῖν,

καὶ τὴν καταρχὴν εὐλόγησον τοῦ σχέδους ~

Τρὶς ἤδη γράφεις, ὦ παῖ, καὶ γένοιτό σοι (8)

ἡ ζωαρχικὴ τριὰς βοηθός, ἵν’ αὐτῆς

τυχὼν βοηθούσης σοι τῷ ταύτης στι-

χεῖν ἐπαίνῳ καὶ ἐγκωμίῳ.

If we include the smaller, interlinear writing as well, we find the following (with the main text here in capitals to aid in distinguishing the two): ΚΥΡΙΕ (ὦ ἐξουσιαστά) ΙΗΣΟΥ (ὦ θεραπευτά), Ο ΘΕΟΣ (τίς: ποιητά), ΗΜΩΝ (τίνων), Ο ΑΣΠΟΡΩΣ (ὁ ἄνευ σπέρματος), ΕΥΔΟΚΗΣΑΣ (τί ποιήσας καὶ θελήσας) ΤΕΧΘΗΝΑΙ (καὶ γεννηθῆναι) ΕΚ ΤΗΣ (ἐκ τίνος) ΑΓΙΑΣ (καὶ σεβασμίας) ΘΕΟΤΟΚΟΥ (τῆς τὸν θεὸν γεννησάσης) ΚΑΙ ΑΙΕΙΠΑΡΘΕΝΟΥ (καὶ ἀεὶ καὶ πάντοτε παρθενευούσης) ΜΑΡΙΑΣ (τίνος) ΤΑΙΣ ΠΡΕΣΒΕΙΑΙΣ (ταῖς ἱκεσίαις καὶ παρακλήσεσιν) ΑΥΤΗΣ (τίνος) ΚΑΙ ΤΟΥ (καὶ ἄλλου τινός) ΧΡΥΣΟΡΡΗΜΟΝΟΣ (τοῦ χρυσολόγου, ἤγουν καὶ τοῦ χρυσὰ ῥήματα φθεγγομένου) ΙΩΑΝΝΟΥ, ΦΩΤΙΣΟΝ (κάθαρον, λάμπρυνον) ΤΟΝ ΝΟΥΝ (τίνα) ΤΟΥ (τίνος) ΝΕΟΥ (ἤγουν παιδὸς) ΤΟΥ ΝΥΝ (ἀρτίως) ΑΡΞΑΜΕΝΟΥ (ἀρχὴν λαβόντος) ΤΟΥ (τί) ΣΧΕΔΟΓΡΑΦΕΙΝ (ἤγουν τοῦ σχεδογραφεῖν· ἄλλο τι) ΚΑΙ ΤΗΝ ΚΑΤΑΡΧΗΝ (τὴν ἔναρξιν) ΕΥΛΟΓΗΣΟΝ (ἐν λόγοις εὔλογον) ΤΟΥ ΣΧΕΔΟΥΣ (τίνα). ΤΡΙΣ (τί ποιῶν· ἐκ τρίτου) ΗΔΗ (ἀπάρτι) ΓΡΑΦΕΙΣ (τί ποιῶν), Ω ΠΑΙ (ὦ παιδίον), ΚΑΙ ΓΕΝΟΙΤΟ ΣΟΙ (καὶ γενηθήτω σοι, καὶ ὑπάρξειε) Η ΖΩΑΡΧΙΚΗ (τίς: ἡ ἄρχουσα τῆς ζωῆς) ΤΡΙΑΣ (ἡ τίς) ΒΟΗΘΟΣ (ποδαπός) ΙΝ’ (καὶ ὅπως) ΑΥΤΗΣ (τίνος: ἤγουν τῆς ἁγίας τριάδος) ΤΥΧΩΝ (ἐπιτυχών), ΒΟΗΘΟΥΣΗΣ (καὶ συνεργούσης) ΣΟΙ (τίνι), ΤΩ (τίνος) ΣΤΙΧΕΙΝ (ἤγουν ἐμμένειν) ΕΠΑΙΝΩ (τιμῇ καὶ δόξῃ) ΚΑΙ (καὶ ἄλλο τι) ΕΓΚΩΜΙΩ (ἐπαίνῳ).

Although, as a rather secular-minded man of the 21st century, we are certainly less familiar with orthodox teaching than was this poem’s author, we wonder if he, or perhaps she, has somehow in confusion given to Mary an attribute of the latter’s cousin’s (Luke ch. 1) or even of the patriarch’s wife (Gen. ch. 18). Likewise, we would expect not Mary & John but Mary & Joseph. (The nomen sacrum here is ἸΩου’, and I don’t think Ἰωσήπου is meant. [Or is it?] An additional confusion, or influence, may be from the epithet’s being ordinarily used, as far as I know, as a synonym of Chrysostom.) Readers: am I missing something? The transcription of σχεδογραφεῖν as its own gloss is correct, as is the accentuation of στ(ε)ίχειν as στιχεῖν. One should very much like to know more about the author (or authoress) of the poem and its addressee! (For σχεδογραφία, which I seem to recall Anna Comnena disapproved of, see here and here.)

~Roderick

Note: I’ve added a new category for tagging, “Manuscript Finds”, for fun stuff like this, and have tagged some of the earlier posts with it.